When Rex Harrison came to Hollywood in 1945 to make a movie, he was 37 years old, had already been on the stage in England for 22 years and had been making films there since 1930. Orson Welles later claimed it was on his recommendation that Harrison was given his first American role, a part that Welles himself turned down, that of the King in the 1946 production of Anna and the King of Siam. Welles told his friend, director Henry Jaglom, over one of their now famous lunches, “I suggested him. Rex made pictures that only played in England, teacup comedies and things. No one in Hollywood knew who he was.” Welles had refused the role, he said, because he didn’t want to work with Irene Dunne, who had already been cast as Anna. And so, Rex Harrison made his American film debut.

![]() |

| Anna and the King of Siam |

At the time he arrived in Hollywood, Harrison was married to his second wife, German actress Lilli Palmer. She also began making movies in the U.S. and started by co-starring with Gary Cooper in Fritz Lang’s Cloak and Daggerin 1946. Both Mr. and Mrs. Harrison starred in 1947 classics - for Rex, the first and best of his three films for Joseph L. Mankiewicz, The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, with Gene Tierney; for Lilli, Robert Rosen’s Body and Soul, opposite John Garfield. Rex also starred in The Foxes of Harrow in 1947; Lilli would star in My Girl Tisa in 1948. Then came the scandal that ruined Harrison’s personal reputation and may or may not have brought him the nickname “Sexy Rexy.”

![]() |

| Lilli Palmer |

Rex Harrison, it seems, was a ladies’ man. By 1947, he had become involved in a romance with actress Carole Landis. The affair was no secret in Hollywood and was apparently made public by columnist/radio commentator Walter Winchell. On the night of July 4, 1948, after Harrison spent the evening with her at her home, Landis consumed a lethal dose of barbiturates. Ruled a suicide, her death was naturally surrounded by a storm of hearsay and speculation. The rumor mill had it that Landis was despondent because Harrison refused to leave Lilli Palmer and/or because he was soon to depart for New York to star on Broadway in Anne of the Thousand Days. There was even some conjecture that Harrison had murdered the woman and staged the scene to look like suicide.![]() |

| Carole Landis |

A few months before Landis’ death, Harrison had completed production on a film for legendary writer/director Preston Sturges. It would be the one-time wunderkind’s final cinematic gem, a darkest-black comedy titled – perhaps unfortunately – Unfaithfully Yours (1948). The lurid and lingering Landis tragedy would have an impact on the fate of the film. In an attempt to distance it from the scandal, the film’s release date was held up for several months. Additionally, publicity was dialed back - and the marketing campaign changed drastically. It was labeled a murder mystery, it was touted as “six kinds of picture all rolled into one” – confusing and misleading the movie-going public.Preston Sturges had written a Broadway hit in 1929 and trekked to Hollywood following the play’s adaptation to the screen. He penned several films for Paramount, including Easy Living (1937) and Remember the Night (1940). In 1940, he asked for and was given a chance to direct as well as write. The result was his political sendup, The Great McGinty, a break-out hit that brought Sturges an Oscar for his original screenplay. A string of sly and exhilarating classics written and directed by Preston Sturges followed, namely: The Lady Eve (1941), Sullivan’s Travels (1941), The Palm Beach Story (1942), Hail the Conquering Hero (1944) and The Miracle at Morgan’s Creek (1944). But Paramount had begun to view its genius-in-residence as next-to-impossible to deal with, and relations between the studio and the man soured. When his split from Paramount finally came, Sturges went into partnership with Howard Hughes on California Pictures Corporation for three disastrous years. Sturges and Hughes parted ways in 1947 and the writer/director soon went to work for Darryl F. Zanuck at 20th Century Fox. Zanuck was interested in a story Sturges had written years earlier titled Matrix. In the end, Matrix was dropped for lack of interest and a treatment of another early Sturges story - he called it The Symphony Story - was picked up instead and retitled… ![]() |

| Preston Sturges |

Unfaithfully Yours bears most trademark Sturges elements – it moves at a dizzying pace, overflows with clever dialogue, is peopled with assorted (and well-cast) eccentrics and its plot completely confounds audience expectations. But in this case, Sturges ventured into especially dark farce…The film opens with the return to New York of Sir Alfred de Carter (Harrison), a well-known symphony conductor, who has been in London. He is warmly welcomed by his beautiful young and doting wife, Daphne (Linda Darnell). But soon mischief is afoot. It seems that before leaving New York, Sir Alfred had asked his rich but dull brother in law (Rudy Vallee) to keep an eye on Daphne while he was away. The brother in law misinterpreted the request and took it upon himself to hire a private detective to monitor her. And now he has come to deliver the detective’s report. Sir Alfred, initially shocked and outraged at the misunderstanding, eventually manages to read the report and works himself into a frenzy of jealousy and suspicion. While conducting a concert after quarreling with his wife, Sir Alfred begins to fantasize about how to handle what he believes is her infidelity. As he conducts three orchestral pieces, he vividly imagines three different possible scenarios – each played out onscreen. The first fantasy involves murder and a frame-up, in the second Sir Alfred is noble and obliging, in the third he falls victim to his own bravado. When the concert finally comes to an end, Sir Alfred sets out to make real one of his fantasies.

![]() |

| Unfaithfully Yours - fantasy or reality? |

Although Sturges wasn’t entirely happy with the film’s final cut (which came courtesy of Mr. Zanuck), he was pleased with the performances – Rex Harrison executes a superb turn as the temperamental artist/bungling schemer. Sturges was also particularly fond of the fantasy segments. He wrote that he tried to construct the three scenarios envisioned by the conductor “as if written and directed by Sir Alfred, who is neither a writer nor a director.” In his fantasies, the conductor imagines his own behavior “vividly” while the other characters are “marionettelike.” Sturges believed this would be “the natural result of Sir Alfred’s ability to have them say and do exactly what he wants them to say and do.”

The film’s themes are dark and, perhaps for the audience of its time, too much so for “six kinds of picture all rolled into one." Its timing in proximity to the leading man's notorious Hollywood scandal was extremely unlucky. For whatever reason or combination of reasons, Unfaithfully Yours was not a success. In his autobiographical notes Sturges reflected, “Unfaithfully Yours received much critical acclaim and lost a fortune.” That the film failed to find an audience contributed to the steep decline of his increasingly precarious career. He would write and direct only one more Hollywood film (The Beautiful Blonde from Bashful Bend in 1949) and it was a resounding flop.

![]() |

| My Fair Lady, with Audrey Hepburn |

Rex Harrison continued to work steadily and successfully on stage, film – and TV – for the rest of his life. He gained worldwide stardom with his performance in George Cukor’s 1964 film adaptation of My Fair Lady, a long-running Broadway hit in which Harrison originated the role of Henry Higgins and for which he won a Tony Award. For transferring his Henry Higgins from stage to screen, he duly took home an Oscar for Best Actor. Knighted in 1989 at age 81, Sir Rex would, as the producer of The Circle, Harrison’s final Broadway play, put it, very nearly die “with his boots on;” his last stage appearance preceded his death, in 1990 of pancreatic cancer, by only six months.Harrison’s long Hollywood career had brought him two Oscar nominations and one win; his even longer career on Broadway brought him five Tony nominations and three awards as well as a special Drama Desk Award in 1985. He was honored with two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, one for film and one for television.

![]() |

| Kay Kendall |

Rex Harrison would also continue to be inconstant in his private life. Sandy Sturges, Preston’s widow, recalled walking in New York with her husband and Harrison in the early 1950s. Suddenly and unexpectedly Rex walked away and left them – he’d spied a lovely young thing on the street and simply followed her. His interest in women, Mrs. Sturges recalled, was “not subtle at all.” Harrison’s marriage to Lilli Palmer continued until 1957, when the two divorced so that he could marry his lover, actress Kay Kendall, who was dying of leukemia. He married Welsh-born, Oscar-nominated, Tony-winning actress Rachel Roberts in 1962. That marriage ended in divorce many years later and, it is said, she reacted by drinking ever more heavily and by finally taking her own life. Harrison was married to the ex-Mrs. Richard Harris, Welsh actress/socialite Elizabeth Rees-Williams, for a time, and his 6th and final wife was Mercia Tinker, to whom he remained married for the rest of his life.

![]() |

| Rachel Roberts and Rex Harrison |

Harrison has garnered much praise for his work on stage and screen, but not much admiration for his conduct out of the limelight. One of his biographers, Nicholas Wapshott (Rex Harrison, 1991) met the actor while researching his biography on British director Carol Reed. Wapshott considered Harrison a “technical genius” capable of “effortless delivery of difficult prose.” He noted that the actor didn’t make much visible effort, “he was inescapably Rex in everything - but his understanding of the text meant that he hit every note the first time.” On the other hand, the author found Harrison, in person, “a cad of the first order,” and at first hesitated to take on the biography of a man whose “black-hole egotism meant he could not appreciate the worth of others, particularly other men, and his attitude to his string of wives…and lovers was often hard and heartless.” Wapshott blamed Harrison’s involvement in the Carole Landis scandal for the fact that Unfaithfully Yours “languished for years.”

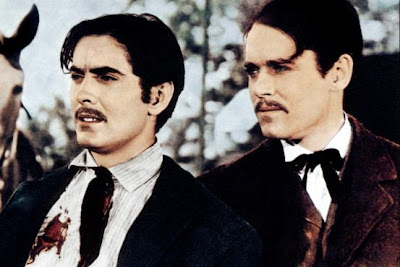

![]() |

| Rex Harrison and Claudette Colbert in Aren't We All |

Tony-winning, Oscar-nominated actor Frank Langella admired Rex Harrison’s work extravagantly; “He was my idol. I thought him the most accomplished, technically perfect, and totally believable English actor of his time.” Langella managed to meet Harrison twice. Their first meeting occurred in the early ‘70s at a cocktail reception in the older actor’s honor. Langella encountered his idol in the foyer where he was removing his hat and coat. The young actor put out his hand and began to extend a greeting when Harrison flung both his coat and his wife’s over Langella’s arm, as if he was a servant, and made his entrance into the party. The two met again in 1984 when a friend of Langella’s was appearing in Aren’t We All on Broadway with Harrison and Claudette Colbert. Forgoing dinner with his friend and Miss Colbert (who utterly charmed him) in order to try once more to pay his respects to Harrison, Langella found him in his dressing room and finally delivered his heartfelt homage. The old actor heard him out and dismissed him with, “Thank you. Very kind. I’m afraid I can’t ask you to sit down.” Langella was not amused and would remember that his good friend, Harrison’s 5th wife, Elizabeth, told him of Rex, “He was the only man I ever knew who would send back the wine at his own dinner table.”

![]() |

| Rex Harrison and Preston Sturges on the set |

British film critic and historian David Thomson‘s view of Harrison the actor is fairly restrained, seeing in most of his screen roles the personification of the stereotypically empty-headed aristocrat. However, Thomson allows that Unfaithfully Yours was “one of the few films that made use of his grating charm.”

Harrison is in top form in Sturges’ black-humored classic, adapting with surprising ease to the writer/director’s penchant for slapstick. Unfaithfully Yours airs on Saturday, August 31, at 3:00pm Eastern/noon Pacific, part of TCM’s 2013 Summer Under the Stars tribute to Rex Harrison.

This is my entry for the 2013 TCM Summer Under the Stars Blogathonnow in progress and hosted by Jill Blake ofhttp://sittinonabackyardfence.com/ and Michael Nazarewycz of http://scribehardonfilm.wordpress.com/. Visit their sites for more information and links to participating blogs.Notes: My Lunches with Orson by Henry Jaglom and Peter Biskind (Metropolitan Books, 2013) Preston Sturges by Preston Sturges adapted by Sandy Sturges (Simon & Schuster, 1990)

The New York Sun, “Unfaithfully Yours, Rex” by Nicholas Wapshott, March 8, 2008

Dropped Names, a Memoir by Frank Langella (Harper, 2012)

The New Biographical Dictionary of Film by David Thomson (Knopf, 2010)